You were first encouraged to create architectural paintings whilst working as an architect for Jeremy Dixon. Can you tell us about this time and what made you devote your career to painting rather than architecture?

It was a very exciting time as the main job in the office was the Royal Opera House refurbishment. Jeremy suggested I paint a view of the housing project I had been working on, Dudgeons Wharf now rechristened Compass Point. We discussed how to approach the painting, not doing the usual slick rendering of a pristine building usually used to sell a project, but to look for the potential sources of realism - where things would go wrong, where brick would stain for example. As I had done much of the external wall detailing, I was in a good position to imagine how the buildings would weather. We decided it should be painted after rain rather than under a cloudless blue sky.

The result was convincing enough for Jeremy to ask me to do something similar for the Opera House. This time, however, the paintings were done as the design was being developed. With Dudgeons Wharf the design and working drawings were finished when I did the painting, although the construction had not yet been completed. There was therefore the opportunity to use the paintings of the Opera House as a design tool, looking at the design through the paintings and seeing what worked and what needed more thought. This only worked because the paintings were very detailed rather than done with a more vague and splashy watercolour approach. The other important aspect of the paintings being in oil was that they could be changed as the design evolved, scratching out and painting over, which was not possible with the more typical watercolour rendering. All this has changed of course with the development of CGI. Although we had CAD to look at building masses and satisfy the planners (who were distrustful of artist’s impressions!), the sophisticated images that can be generated now were still things of the future.

As to why I decided to devote myself to painting rather than architecture, it is what I had always wanted to do. Architecture was my father’s suggestion for having a respectable career rather than struggling as an artist. Not an unfamiliar story I think. I remember when I was applying to Cornell’s architecture school, I knew nothing about architecture. The interviewer sent me around to see some architect’s offices so that I might have some idea of what I was getting into, and in one of them I met the guy who did the renderings. I thought this was the job for me! I forgot all about that in architecture school as I became indoctrinated into the modernist approach to design which did not encourage romantic images of architecture but a more engineering type of attitude. I carried on painting all this time but kept it to myself. This is why I had great reservations about how the paintings of the Opera House would be received, not so much by the public but by the profession.

I suppose another aspect of why I chose to switch to painting was the length of time it takes to get a project like the Opera House built. Jeremy won the competition to redevelop the Opera House in 1983 I believe, and it was not completed until 1999. Even very long painting projects like my Lutyens painting, which took three years, are much, much shorter. There was so much time spent waiting. Sandy Wilson spent 30 years on the design of The British Library and in that time the concept of the library totally changed.

I also suppose I was a rubbish architect.

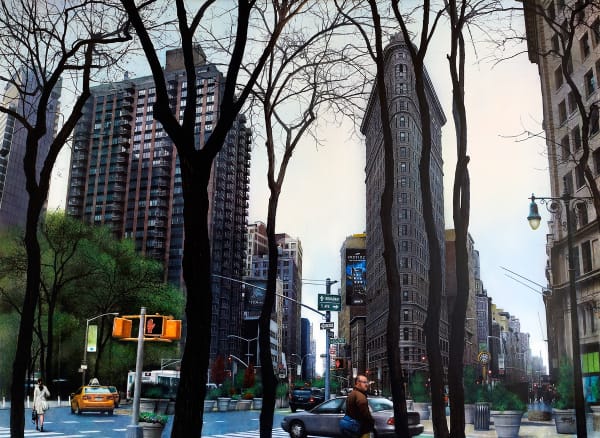

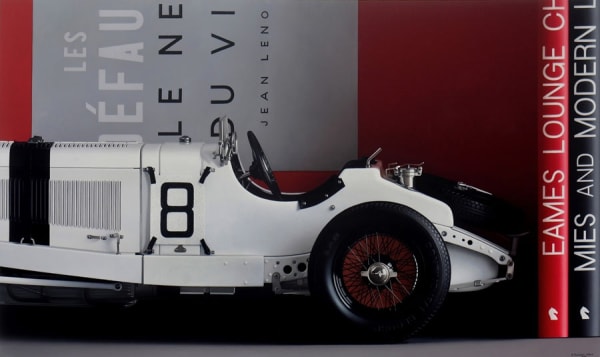

'Gratte- Ciel', 2015 oil on canvas, 41 x 30 cm

What is your artistic process?

I don’t really have a set process. I tend to look at each new painting as a unique problem and deal with it in the way I think it wants to develop. I suppose that is the influence of my architectural past. One of the things I enjoyed about architecture was the fact that with every new job came a new set of problems, a new group of people to work with and in the best cases a new realm to become familiar with and explore, working with people who are experts in that field. It can be the same with painting and I really love starting a new project with that feeling of not knowing what is to follow. Yes, you bring some experience to bear on what you do, but not follow a formula of how to proceed.

Also from architecture comes the importance of drawing to my painting. If there is anything like a set process it is that the subject is explored and developed in drawing first before being committed to canvas. It may totally change in the course of painting, but the better the drawing, the better the painting I feel. If it begins with a poor drawing, my time is spent trying to correct the errors of the drawing in paint.

You are very well- known for painting architectural Capricci, which has obviously stemmed from your background as an Architect. Do you feel painting allows you to pursue architecture in a much freer way?

Of course. Painting allows you to concentrate on form without any of the numerous problems that an architect faces from gravity and water to planning policies. This could lead to superficiality so I think it is important to be aware of the complexity and many facets of architecture even when indulging in the freedom of architectural fantasy.

Could you explain what a Capriccio is?

Not easy. It is most simply a fantasy or a composition that combines real and imaginary elements, but there are so many interpretations of that. I remember going around the National Gallery with someone who was interested in doing an exhibition on the architectural capriccio. I think the majority of the paintings we looked at had an element of capriccio in them. It is almost a definition of painting. As soon as you start tampering with an image, you are in the realm of the capriccio to my mind.

The idea of capriccio that is most meaningful to me and is generally understood is one where architectural elements, be they buildings or details, are taken out of context and given a new imaginary setting. Think of Canaletto painting imaginary bridges (actually designs by Palladio) on the Grand Canal or William Marlow painting St. Paul’s Cathedral repositioned on the Grand Canal (The Grand Canal is not crucial for something to be a capriccio!). But really, any painting of an unbuilt building is a capriccio as it is a fantasy until it is built.

'Klenzeana, The Architecture of Leo von Klenze, 2016' oil on canvas, 140 x 240 cm

'Klenzeana, The Architecture of Leo von Klenze, 2016' oil on canvas, 140 x 240 cmYou have many series of paintings dedicated to specific architects, is this a way of studying the architect’s work in greater detail or a way of honouring them?

Both as I would not paint the work of an architect I did not feel deserved celebrating. But the greatest enjoyment is in painting buildings which were never built or have been lost, trying to understand what the architect was trying to achieve in his drawings and how that would translate into a built structure. For instance, it was a great challenge to paint Lutyens's design for Liverpool Cathedral. There are so many varying depictions in the drawings, the model in Liverpool and Thiepval Memorial which shares many of the same details. All these needed to be considered in working out what the Cathedral might have looked like. Hopefully it also honours Lutyens’s conception of the Cathedral. It is almost like being an assistant in these architects’ offices, as I immerse myself in and become familiar with their work.

How do you select the architects you research?

Usually I choose architects whose work personally appeals to me, but often I have taken on suggestions from others. My first capricci were suggested to me; Jean Dethier of the Centre Pompidou asking me to paint the Grands Crus Chateaux of the Médoc for an exhibition at the Pompidou, a friend asking for a painting of Palladio’s buildings after seeing the Chateaux painting, and Richard Stilgoe asking me to paint Wren’s architecture after seeing the Palladio painting. All of these were welcome suggestions as they led to the study of and eventual familiarity with some wonderful architecture, and you can see how a sequence of paintings develops naturally. C.R. Cockerell was an obvious subject having painted capricci himself and was due for a similar treatment. Ledoux was also an obvious choice as so little of his architecture was built or survived that it was an interesting challenge, just enough surviving to give an idea of how the others might be. Ledoux was especially interesting as he drew so many impossible situations - impossible to build or construct in three dimensions. I chose Lutyens on visiting Castle Drogo without knowing anything like the extent or variety of his work, but just enough to know it would be fascinating to discover. The von Klenze paintings in the current exhibition were the result of a suggestion by David Watkin at a dinner party.

'Bathing Pavilion, Tyringham, 2014' oil on canvas, 31 x 36 cm

Your paintings tend to be of classical architecture and sculpture, but in your most recent paintings more modern glass clad buildings seem to be appearing. How has your work evolved over the years? Is modern architecture something you may pursue?

I have painted both modern and classical architecture throughout my career and intend to continue to do so. It is a matter of good architecture, architecture that moves me, excites me, not of period or style.

Your work ‘Metiendo Vivendum (By Measure We Live), A Tribute to Sir Edwin Lutyens’ is so detailed and large, how long would it take to produce a piece like that and how do you approach it?

It took three years from visiting Castle Drogo and the decision to do a Lutyens capriccio to the finished painting. At first I made random visits to Lutyens buildings as I came across them in my initial readings about him. It became obvious that there were so many designs that a more methodical approach was necessary and I set off on several Pevsner-like expeditions to track down his buildings which I drew up individually. As the numbers of buildings grew, types began to emerge which eventually became groupings in the painting. When I constructed a drawing of Liverpool Cathedral I became aware of the comparative size of it and that was a significant point in developing a composition as it led to the decision to draw everything to the same scale. The composition then evolved slowly around the Cathedral in the centre with swathes of related buildings moving around it.

‘A Sentimental Journey’ is the title of your current exhibition at Plus One Gallery. The title is reference to a satirical novel of that title by Laurence Sterne. Could you briefly explain the connections between the two?

I surprised myself by the choice of title as I dislike the overused term journey almost as much as the word iconic, but Sterne’s 'A Sentimental Journey' seemed relevant to me. It is a novel about the 18th century Grand Tour where British aristocrats, and more modest travellers if they found sponsorship as well as travellers from other European countries, journeyed through France and Italy and occasionally on to Greece immersing themselves in the sources of western culture. The novel contrasts the the open-minded traveller willing to learn from his travels with the superficial and reluctant traveller going through the motions of visiting the obligatory sites. As the book is about a willingness to discover, an open mindedness, I felt the title was relevant to looking at the architecture of Leo von Klenze who is virtually unknown in Britain and Le Corbusier whose architecture is largely disliked in present day Britain.

Leo von Klenze actually went on the Grand Tour or a version of it, on two occasions, studying, in depth, antique sites in Italy and Greece and at one point working in France. He was definitely a Grand Tourist determined to make the most of his tour. Many of the sites of the Grand Tour had an enormous influence on his architecture. It was from the drawings and paintings of Italy and Greece that von Klenze produced on these trips in a book given to me by Léon Krier that I first learned about him. These sketches and paintings demonstrate the openness to experience, portrayed in 'A Sentimental Journey', as they come to influence von Klenze’s own architecture.

I think Le Corbusier’s architecture is now ready to be revisited with an open mind, looked at in the same way we look at the historical styles visited in the Grand Tour for what we can learn from them. He can now take his place in that historical sequence of styles. And going back to his architecture is in a way a sentimental journey for me, returning to my architectural roots at Cornell.

This exhibition also includes more urban architecture, an area we have not seen you focus on before. You explained previously that these pieces were influenced by fellow architect Léon Krier, he produced sketches for a project he invited you to work on. What is this project and how do you visualize the exhibition at the end?

I think that urbanism has been important in my painting all along. The Opera House paintings were very much concerned with urban space and how it is used, and I depicted Léon Krier’s Atlantis project in 1987, which was an essay in urban design. Paternoster Square paintings done in 1988 were concerned with the urban design of the area around St. Paul’s. There is a large element of urban design that comes into Klenzeana, the painting in this exhibition depicting the major works of Leo von Klenze. In an effort to show the complexity and extent of his design for extending Munich in the first half of the 19th century, I have taken a viewpoint above the area he redesigned so that the plan can be understood. This has essentially dictated the composition, with individual buildings then located higher up, closer to the viewer where they can be better appreciated. The new paintings featuring Le Corbusier’s Pessac housing were intended for a project of Léon Krier’s revisioning Le Corbusier’s Cité Henri Fruges, a 1925 housing development for the workers in Henri Fruges’s sugar refinery. This forms part of a larger Krier project to create a 9th volume of Le Corbusier’s Oeuvre Complete subtitled: “Le Corbusier after Le Corbusier; LC Translated, LC Completed, LC Corrected”. Léon Krier appears to be a unifying thread running through this exhibition, having introduced me to the work of von Klenze back in 1987 and initiating these new Pessac paintings. Whether the intended exhibition Léon planned, 'Le Corbusier after Le Corbusier', will ever take place, I don’t know. I think it is a bit of a “hot potato” and no one seems willing to take it on. It is again an instance of the sentimental traveller being willing to look with openness and a willingness to learn. Léon has looked at Pessac and identified where he feels it could be improved. As built it is only suburban housing. Le Corbusier designed a second phase that would have included the amenities that would have raised it to something equivalent to a British Garden City, but this was never built. Krier’s project looks at hypothetically introducing those amenities and also reorganising the buildings to give a hierarchy of spaces rather than simply a pattern of streets lined with houses. This was one of the aspects I found it hardest to get to grips with in the paintings as the buildings at Pessac are quite charming, now 91 years old with lush gardens. To alter them so they are facing onto paved squares without the buffering of their gardens was a dramatic move, but one that gives more of a lively urban feeling than found in suburban dormitory housing. Pessac is only one of Le Corbusier’s projects Krier has looked at and hopefully all the work he has done to create a 9th volume of Le Corbusier’s Oeuvre Complete will be exhibited at some point, beautifully illustrated with his distinctive drawings.

'Machines for Living III, 2015' oil on canvas, 51 x 122 cm

To book an appointment or for more information please contact us via email on maggie@plusonegallery.com and maria@plusonegallery.com

or by phone on 020 7730 7656.

or by phone on 020 7730 7656.